The Arctic Monkeys' debut album picked up almost every music prize going, so it's little wonder that its follow-up, out this month, is set to become one of the year's most important records.

Michael Odell

meets the biggest band in Britain.

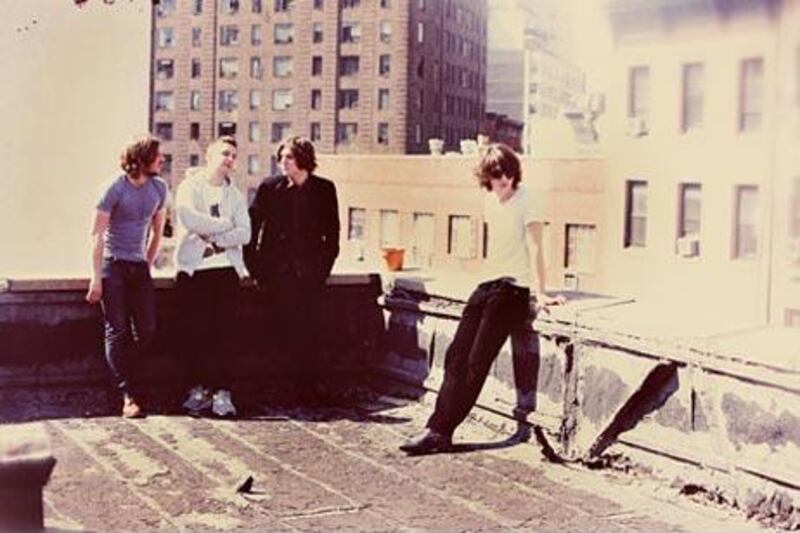

'I still miss the days when a haircut was just a haircut. It was only your mates you had to face. Now there's a whole industry centred around people analysing your 'look'. I just cannot understand how anyone could get so worked up by. hair." Arctic Monkeys frontman Alex Turner is sitting in an east London bar bemoaning the fact that his recently upgraded coiffure has not really worked for two reasons. A) hawk-eyed fashionistas detect that the recent move from "bird's nest" to new flowing locks signifies a move from indie to hard rock and he has been forced on the defensive. B) Everyone else just thinks he looks like a girl.

"I think there might be some truth to that, to be honest. I've been told I look like a 17-year-old Spanish girl. From the back, that is. When you get round the front it's obvious I'm just a... bloke." As the rest of the band file into the bar it is clear that "just a bloke" is the preferred social operating mode for the Arctic Monkeys. They may be one of the biggest and certainly the most influential UK bands in the world but it is mid-morning and there is nothing but indefatigable dourness on offer.

There are mumbled greetings of, "Awright mate". Fists are pushed firmly into the pockets of trousers or anoraks. Bass player Nick O'Malley and guitarist Jamie Cook prefer to make close and detailed inspection of the furniture than make any sort of eye contact. Alex Turner on the other hand is an inveterate fiddler with keys or phone while he talks. Otherwise he has the slightly unnverving habit of staring at you unblinkingly with his dark brown eyes, like a curious young horse. Thank goodness for the Arctic Monkeys' secret weapon: drummer Matt Helders, the closely shorn, chirpy raconteur who could stroll on to any TV set and anchor a game show without any preparation whatsoever. Without him I fear that most Arctic Monkeys interviews would be glorified staring competitions.

"It's great to have something to talk about again," says Helders effervescing in directly inverse proportion to his band-mates' dourness. "I mean, apart from Alex's hair we've got a new album and we're very excited about the fact that no one's heard it and.and. it's just really good to know you've done the best music you've ever done." The other Monkeys concur with this by briefly looking up from their mobile phones before resuming texting or yawning. To be frank, as an outsider it doesn't appear to amount to very much: four young British musicians sharing in-jokes, sullenly answering the odd question or examining dust particles in the sun rays through the window. You have to remind yourself that this is it: the creative epicentre of British rock for the past five years. They might not be much in the way of a thigh-slapping get-together. However on CD they make absolute sense and an unforgettable impact.

The Arctic Monkeys formed in 2002 in High Green, an unremarkable suburb of Sheffield, a former steel town in the north of England. When Alex Turner received a guitar as a present the previous Christmas he had the brass band musical know-how of his father to draw on. But he also had the innate shyness that he still struggles with today.

"We did try another lad out as the singer but he choked when it came to show what he could do. There was no way that I wanted to be the singer. The band that we followed at the time was The Strokes and they seemed too cool for school in every way. I didn't feel I could live up to that. Even when I finally got round to writing my own lyrics I had this sense of dread that the others would laugh me out of the room. Mickey-taking is a useful quality control and I never thought I'd get past that, to be honest."

But of course they didn't tease him for long because it's no exaggeration to say Turner immediately showed signs of a precocious song-writing talent. As a teenager he had worked behind the bar at The Boardwalk the famous Sheffield venue and watched punk poet John Cooper Clarke perform. He began making notes in between serving drinks and washing glasses. By the time they had signed to independent label Domino and released their debut single I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor, the band had allied their spiky rock to Turner's acutely observed but eminently shoutable lyrics.

Frenzied crowds singing "I bet you look good on the dancefloor/Dancing to electro-pop like a robot from 1984" were proof the Arctic Monkeys had come from unwrapping their first musical instruments and learning to play them to genuine cultural reference point in four years flat. Their debut album in 2006, Whatever You Say I Am That's What I'm Not, is the biggest-selling British debut album of all time. On tracks like the laconic Riot Van Turner depicted a desperate Saturday night on a UK high street with wit and sadness.

When I followed the band on their UK tour that year it was clear huge audiences felt they were watching "the new Oasis" reflecting their own lives back at them. Even the prime minister Gordon Brown (then chancellor of the exchequer) cringe-makingly tried to show off his credentials by telling a women's magazine the band's music "really wakes you up in the morning". If they were a boy band, they'd gush at such memories. But as a "proper rock band" it's a code of practice to disown past achievements. Besides, history has already recorded things wrongly as far as they are concerned. For example, they were supposedly the band who rewrote the rules of the music industry by appealing to their young fans over the heads of the music business via the internet.

"We'd love to take the credit for that but we can't," Turner says. "It would seem wrong to claim we used the internet as a tool of subversion when most of us can barely get an e-mail, let alone set up a website. The truth is, back in the early days, a mate put a couple of our songs up on the internet and people downloaded them. I don't think any of us even knew how to do that. All of a sudden we are the pioneers of a new industry model, or whatever people want to call it. And when the media decide that's what you are there's little choice but to sit back and soak it all up."

What you don't get with the Arctic Monkeys is anything extra-curricular to buy into. There is no offstage panto like Oasis's Gallagher brothers to keep the media interested. Catwalks, tabloids and red carpets all remain largely Monkey-free zones. Off-duty, they go back to their homes in Sheffield. All except Turner, who last year bought a house in east London which he shares with his TV presenter girlfriend Alexa Chung (the pair now also have a base in Brooklyn, New York, where she is working on an MTV show).

But have they backed themselves into a corner with the air of a band who cannot quite tell the difference between cool and sulkiness? They refused to go on now defunct UK television show Top of The Pops. They refused to attend the 2006 Brit awards and accept their prizes (they relented in 2007, appearing on video link-up inexplicably dressed as characters from The Wizard Of Oz). But their biggest mistake was at the 2007 Q Awards. Turner decided to break his shy and retiring demeanour to launch a verbal attack on Take That, who were seated in the ballroom in front of him.

"A lot of people make jokes about having awards for no reason just for the sake of having awards, and pretending they were good when they weren't. I'm not old enough to know a lot of them, but even I know Take That were b*****ks," he said. Far from voicing popular dissent, Turner looked as if he was bashing an-all-too easy target. Even more embarrassingly, Take That were big fans of the Arctic Monkeys and were genuinely hurt by the public insult.

"Mark Owen is the nicest man in the world. I've met him a couple of times since. I was badly behaved that day. He understood. There was lots going on and we needed something to say. Cantankerous youngsters getting overexcited on the big occasion." he explains today. "I really want to be friends with Gary Barlow," adds Matt Helders. "I'm not joking. I've seen him on telly a couple of times and he seems like a great laugh."

There are other encouraging signs of a healthier engagement with the world, too. In the UK, the band are due to release an exclusive 7in vinyl version of their new sing Crying Lightning through the Oxfam charity shops. Odd that a tale of sinister teenage longing should end up funding international relief projects. It's certainly a departure for the Monkeys. Previously they have seemed wary of "causes", such as 2005's Live8, which both Cook and Helder told me at the time would have been "impossible to do without feeling a bit of a hypocrite".

Without drummer Matt Helders, the Arctic Monkeys would still be a great band. However the drumming would probably not be quite as visceral, and it's hard imagining them having quite as many friends. Helders holds all the band's feel-good social skills. It is he who writes the best band blog. It is he who wears the zaniest attire. Even more impressively, it is he who managed to make friends with R&B kingpin P Diddy and create one of the most heartwarming YouTube clips of the year: the pair making a late-night omelette at P Diddy's Miami bungalow.

"I went to Miami with [Arctic Monkeys producer] James Ford, who was DJ'ing at P Diddy's party. Afterwards we went to his house and James introduced me properly. It's a bit disconcerting because you're not sure whether to say 'Hi Puff' or 'Hi Diddy' and then he just says 'Hi, I'm Sean'. Anyway, it turned out P Diddy knew the band. He was like, 'Aw man, I love those Arctic Monkeys!' and he gave us a tour of his bungalow. He was a great man. I was a bit disappointed I didn't meet his butler, though. I heard a lot about him and I wanted to put him to the test, ordering a strawberry milkshake at 4am or something. He's supposed to be the butler who can fulfil any task and I wanted to see if I could test him to his limits."

Though they are undoubtedly members of the indie rock elite, it is still remarkable that P Diddy had heard of Helders and his band. The Arctic Monkeys are still to have any major impact in America. But that may change with the release of their new album. Humbug doesn't explicitly state its ambitions. But the fact that the band felt the need to acquire the help of Queens Of The Stone Age's Josh Homme, leave the UK for the Mojave Desert, grow their hair and get louder suggests that change is afoot. Humbug still hauntingly captures the strange science of youthful romance, and Turner can still write a lyric which seems to articulate emotions way beyond his years. (My Propeller, for example, advances an elaborate analogy for an emotionally stunted man who needs someone else to get him started.)

But it is louder and has somehow lost the tinny UK indie trappings which make so many British bands unpalatable to the American mainstream. Have the Arctic Monkeys consciously fashioned something brasher, bolder, more international and exportable? "I can honestly say I don't think we have ever sat down and made a plan beyond what songs we are going to play at a gig. I'm sure there are people at the record company who have sleepless nights about what markets our albums might do better in, but I don't understand that kind of thinking myself: 'I'll add a heavier guitar sound because they'll go for it in the Mid West'. Nah. That's rubbish. There's no way we could try and make a record for anyone except ourselves."

Turner, though, has broadened his horizons. One of the most acidic attacks of their debut album was Fake Tales Of San Francisco on which Turner mercilessly lampoons a wannabe rock band for trying to be American. "You're not from New York City, you're from Rotherham" he scowls. Needless to say, Turner is being reminded of these lines almost daily these days. "I'm sure I've said things which I regret but the lines to that song aren't an example really. At the time there were a lot of bands who wanted to be like The Strokes and they thought the way to achieve it was by trying to sound American. I don't think I would ever recommend that. Hopefully we have been influenced by all kinds of music but added something which is about our own experience to the music."

You have to admire Turner. It's as though the Arctic Monkeys will only partially satisfy as an outlet for his talents and he seems determined to grab all opportunities to come his way, however risky. In 2007 while other band members took a well-earned rest he announced a side project with his friend Miles Kane from unknown band The Rascals called The Last Shadow Puppets. The pair retired to rural France with producer James Ford and recorded a collection of lush strings-laden '60s-style pop tunes. The Age Of The Understatement became a number-one album and a successful tour, with the London Philharmonic Orchestra followed.

"Sometimes it can be a pressure being the fellow in the band who writes the songs. Getting together with Miles I've got someone to bounce ideas off and that is something new for me. It's quite an intense thing writing by yourself and it felt good to share it with someone that I totally respect and trust. Also, it gives me somewhere to hide because he's up there singing with me. In the Arctic Monkeys, there's nowhere for me to hide."

Given that the side project proved so successful, it is likely to resume at a later stage. Talk turns to Jack White of the White Stripes who currently has three bands on the go simultaneously. Is Turner becoming a songwriter of comparably prodigious vision and energy? "I wouldn't say that. I just like the idea that you don't ponder things too long and you keep moving and keep trying different things. The rule is: keep wriggling or die. I never wanted to be in a band where you get sick of seeing each other. You heard about these groups that go away to a Caribbean island and they can't think of a single idea for a song and they all hate each other. I never want to feel like that. Like it's a chore. I feel refreshed for having done the Puppets album. It gave me a whole new insight into songwriting and more confidence as well."

Last year Matt Helders curated a CD entitled Late Night Tales in which the drummer collected his favourite "late night" music together. He asked Turner to write and read a short story for inclusion among the music choices. A Choice Of Three, a monologue exploring various reflections in a train carriage window, was the result. There are not many rock stars who could pull that off. Is this the beginning of more formal literary output from Turner?

"No, I'm a long way off that," he says. "There's a world of difference between imagining a relationship over the span of a four-minute song and writing a proper story about it. I really admire people who can write with quality for a whole book or a film or whatever. I don't think I'm anywhere near that. But never say never." There is a sense that though Turner writes so well about the louche life of the UK's urban underbelly, that he is not wholly a part of it. Whereas Oasis are indistinguishable from their audience, Turner is a writer who isn't quite committed to the life whence he came.

"I'm restless," he says. "I'd like to think I know who I am but I'm interested in the world at large. Doesn't matter where I'm living. I've got a pen and a notebook I bought in a market in Manchester. That's all I need."

Humbug is released on August 23.