"I was 18 years old when I started driving trains," Lebanon's last living train driver, Assad Namroud, 92, recalls. "My father was a conductor. I was taking my exams in school when I stopped going.

"My father found out and said he was going to enrol me in the railway and they accepted me straight away," he tells The National. "I was young and strong back then."

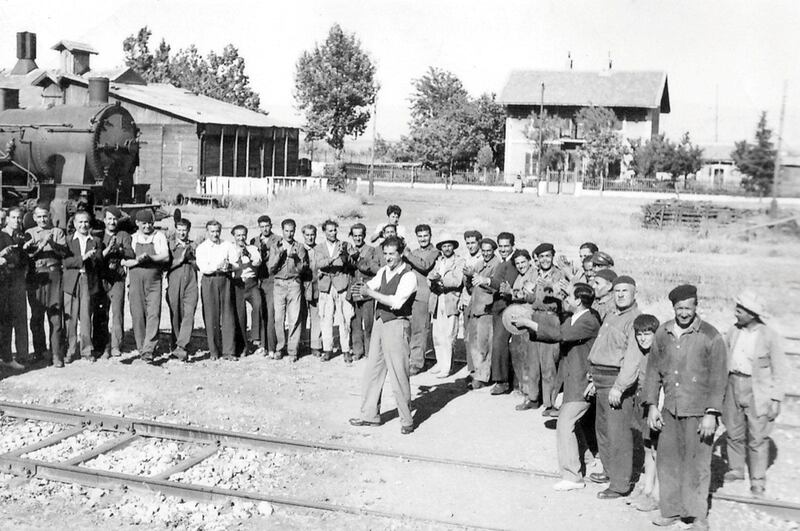

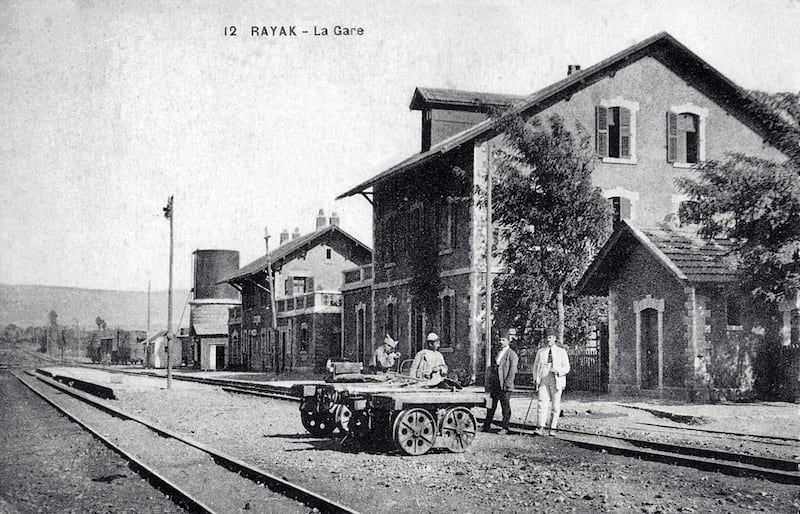

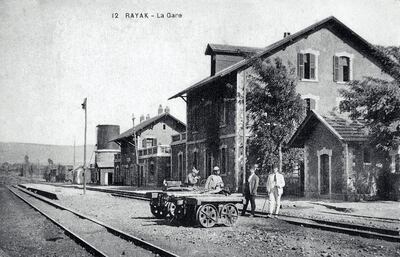

Born in 1928, Namroud served the state as a conductor for almost half a century, at a time when Lebanon's rail system was a golden-age symbol of prosperity and innovation. His home town of Riyaq, in the Bekaa Valley, once held the area's main train station, a vibrant hub of activity sprawled across 35,000 square metres.

Trains in Lebanon: an important, but distant, memory

Lebanon's first locomotive set off down the Beirut-Damascus line on August 4, 1895, which recently celebrated its 124th anniversary. Built under the Ottoman Empire rule, it was part of a rail network spanning three continents.

The Lebanese Civil War (1975 to 1990) ground the country's rail transport to a halt. Today, all that remains of this bygone era are eerie, dilapidated stations dotted with rusting steam engines.

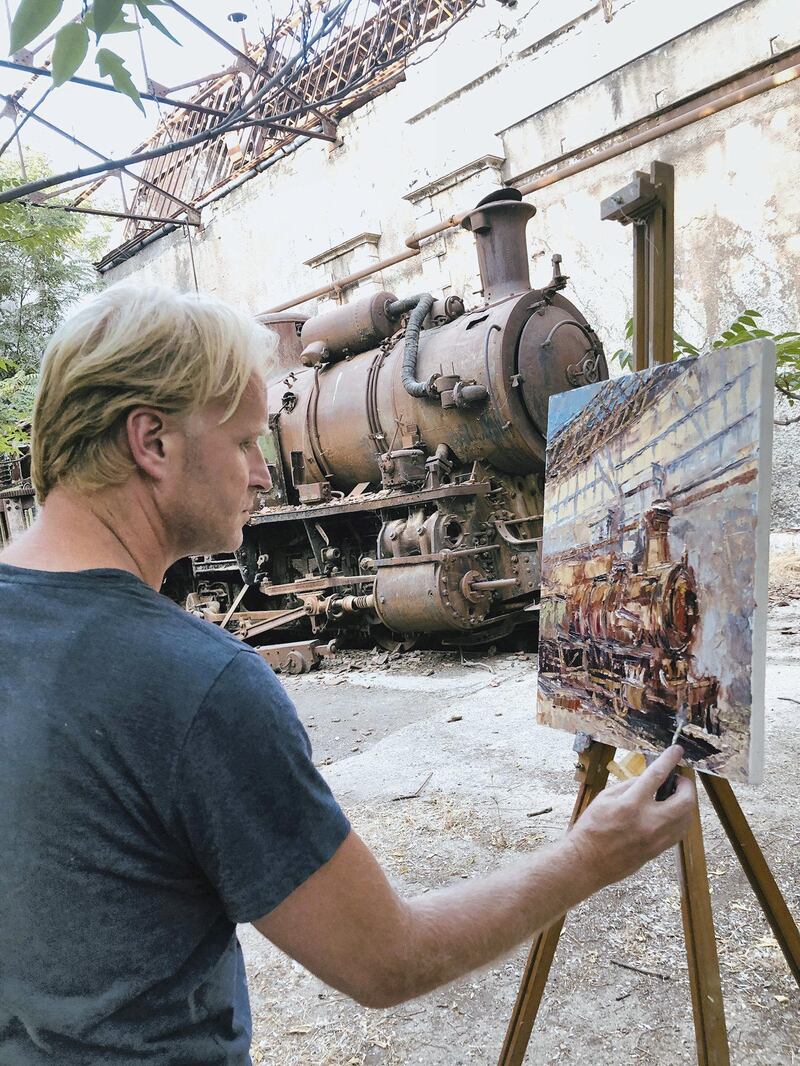

The Riyaq Station, which is usually closed to the public, was recently opened for an artistic intervention, hoping to raise awareness about the heritage these stations hold, despite them being left to wither away with time. Paintings by British artist Tom Young and photos by Lebanese photographer Eddy Choueiry were exhibited.

"Look at all the trains. They're all broken and left to rot, parts have been stolen and they're unhooked," Namroud says. "My train is still here, it was called the 300 SSS. Every time I visit here I kiss my train; she was a machine that we worked with for 46 years and six months."

Parked in the station's factory, where trains from the entire region were once repaired and outfitted, Namroud's train and its surroundings have been reclaimed by nature. Trees have sprung up between the broken glass and crumbling walls. Oxidised wheels, machinery and the odd railway maintenance car dot the complex, half-hidden greenery.

“It was good times back then, we were happy, living lives of simple comforts and living right,” Namroud says of his heyday. “We used to go from Riyaq to Halab, from Halab to Turkey, pick up another train from Turkey and bring it back to Lebanon.

“I used to go for a whole month to get from here to there,” he says. “I would take containers of materials for the government, mostly phosphates, back to Riyaq, where they would be sent to Beirut and packed on to ships.”

Namroud remembers his career fondly and revels in past memories

Namroud's early career was spent making random train runs all across the country. It took five years until the French Mandate approved his licence.

Upon receiving some of the highest scores in his class, Namroud was asked to take other trainees and workers under his wing, including much older people who had been in the industry for decades. Aged 25, he was assigned the 300 SSS and began driving the harsh Dahr Al Baidar line.

"There was a long tunnel and black fumes from the train would get trapped in with us," he says. "Sometimes I would come out coughing up black.

"We had doctors waiting for us at the stations but really, what good did it do? We still had to breathe in the smoke the next drive through."

Despite the harsh reality of running a steam engine, Namroud remembers his career fondly and revels in past memories. He enjoyed driving passenger runs and taking people up to the mountains for picnics or to see the winter snow in Dahr Al Baidar.

The chatter and excitement of children or groups of ladies passing the time smoking their arguilehs (hookahs) on board are still sharp in his mind's eye, as are the simpler moments of his youth.

Namroud readily tells the story of a summer day when he collected his salary and decided to treat his contractor and himself to ice cream.

“We walked into a corner shop to get sweets and ice cream and a young boy there turned to his mother and said, ‘Look, that’s the train driver who used to light the coals for your arguileh,’” he says. “I used to take a piece of coal from our engine and give it to them to use. When I came to pay the bill for our sweets the woman said, ‘Your bill has already been paid and will be any time you come for ice cream.’”

'My heart was cut to pieces when I heard that the trains were stopped'

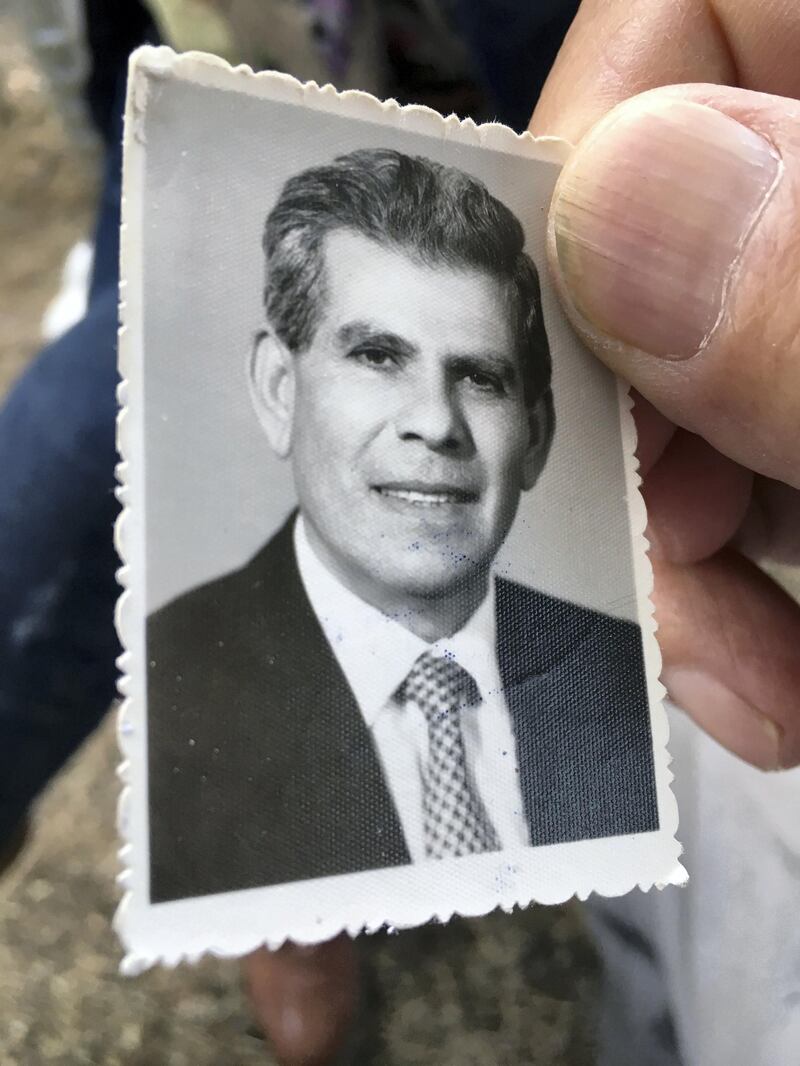

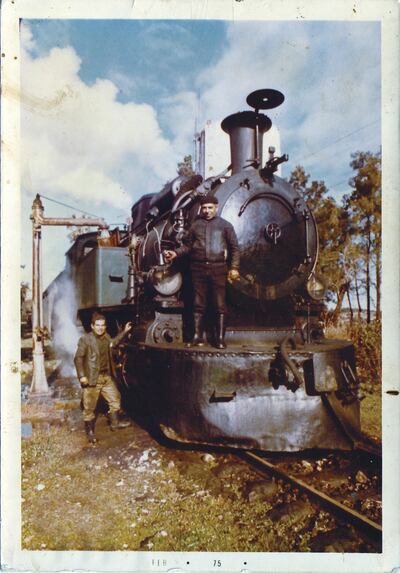

Namroud keeps a small portrait of his younger self in his wallet, eager to show anyone who asks. He says a large photo of him also sits in Beirut’s Rafic Hariri International Airport.

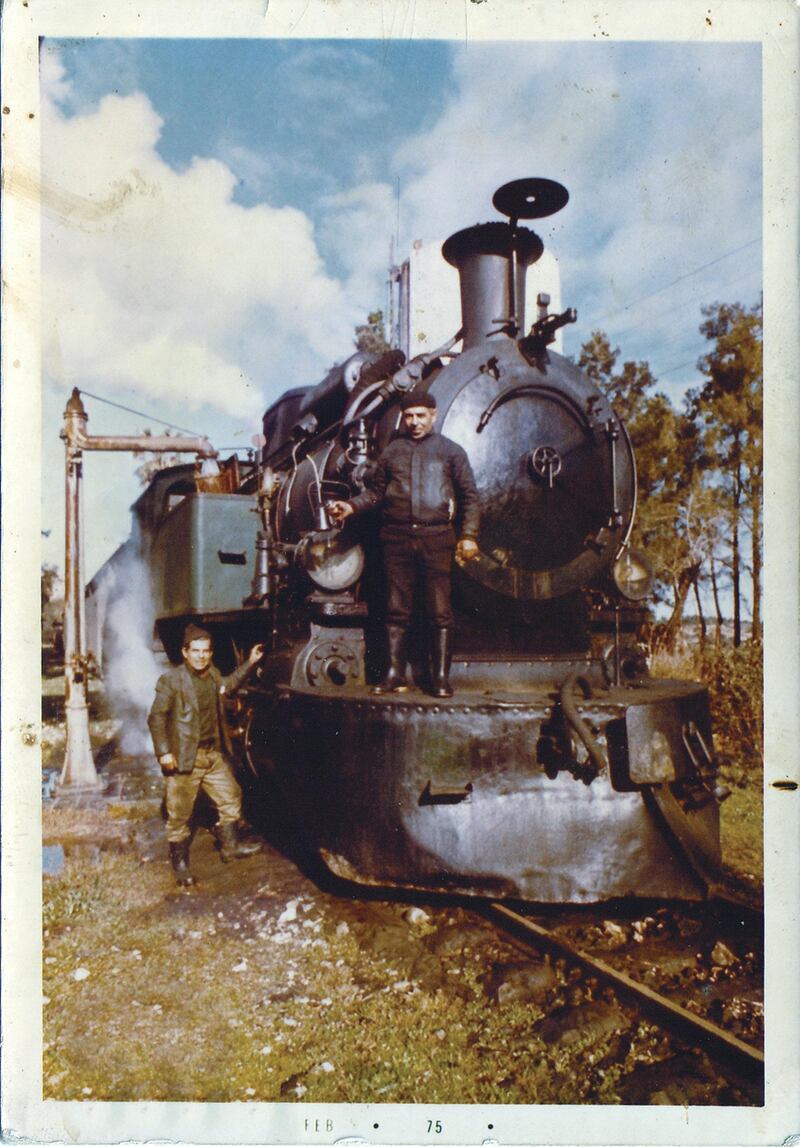

“This photo is everywhere now,” he says, gesturing to a copy of the sepia snap of himself, standing young and proud next to his train in a brown leather jacket. “I remember when we took this photo – I told my contractor to go out and polish the glass and turn on the lights because we were about to pull into Riyaq.”

In 1976, Namroud parked his train in Riyaq for the last time. Many of the country’s railways were stopped due to the war and, in 1992, rail travel ceased completely. During the conflict, Riyaq Station became a military base for the Syrian army, where they remained until 2005.

"I felt my blood freeze and my heart was cut to pieces when I heard that the trains were stopped," Namroud says. "Eleven thousand workers were let go, paid their wages and discarded. It wasn't fair."

Though the rail system has largely been forgotten by the state, NGO Train/Train Lebanon seeks to protect what is left of that era and to help get modern railways added to Lebanon's mediocre level of public transport.

Thousands of people commute by car to Beirut every day from as far as Tripoli, unable to afford the exorbitant housing prices of the capital. Motorists trickle slowly towards the city during rush hour on a good day, crawling along the main highways.

“When we saw the state of these stations we had to do something,” Train/Train Lebanon’s vice president Nabil Doumani says. “We’ve made plans for the return of trains, specifically the coastal Beirut–Tripoli–Syrian Border line. With luck it will go to parliament and maybe get voted on.

“Trains are now environmentally friendly and a small train can transport 2,000 passengers or 600 containers of goods,” he says. “Imagine how much they would reduce traffic on the coastal highways alone.”

Namroud says he is not optimistic about the return of Lebanese rail but hopes he is proven wrong. "You never got to see days like those, God help you," he says. "I ask for the trains to return for you, for the young generation. My time has passed, but if they do return, I'll be in line to drive the first machine they start up."