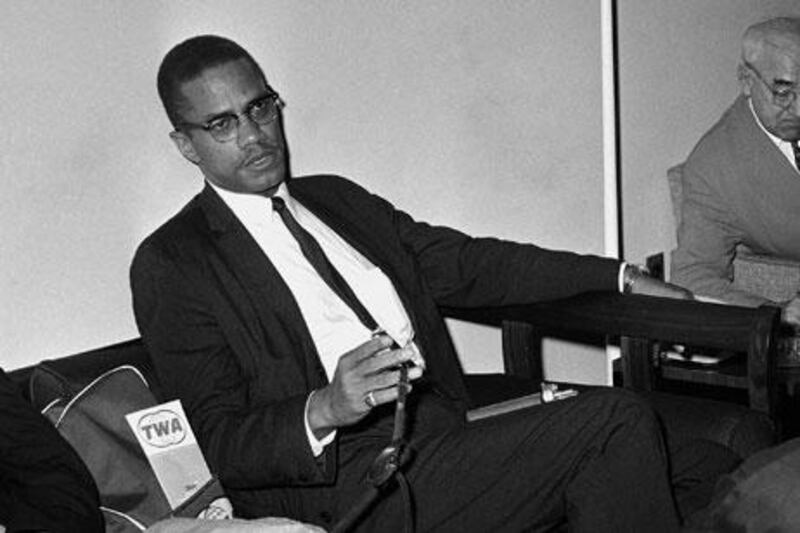

In the most paranoid recesses of the American imagination, militant Islam has taken a number of forms, nearly all of them foreign, bearded, scary. So in the present age of supposed underwear bombs, dirty bombs and dirty-underwear bombs, it's easy to forget that the scariest Muslim figure in the United States before Mohamed Atta wore a crisply pressed, martinised suit, spoke English (though no other language) magnificently, and was born with the innocent-looking American name Malcolm Little. Little, who was assassinated in 1965 at the age of 39 by a fellow member of the religious sect he had just left, was better known as Malcolm X - the X marking the spot where his real name would be if his ancestors had not been enslaved and relabelled by their owners.

Most Americans now know him from The Autobiography of Malcolm X, a posthumous volume "told to" the author Alex Haley. The book, a classic of redemption literature, tells of troubled youth, violent criminality and religious conversion during a long spell in prison. Once on the outside, Malcolm's charisma brought enormous success in harvesting souls for his new faith and in leading, through the 1950s and 1960s, the last serious black separatist movement in the US. To this day, his name is counterposed to Martin Luther King's, with King remembered for reconciliation and Malcolm for his uncompromising rejection of white America.

Haley's book is now part of the American literary canon and makes frequent appearances on US secondary school reading lists. (One wonders how many lazy US schoolchildren have read only the first half, with its deeply strange religious heterodoxy, and come away with warped views of Islam.) The Autobiography is also, in many of its details, fudged and rigged to make Malcolm's spiritual progress look cleaner and more vivid than history shows. Manning Marable's new biography, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, is therefore a work of commentary on the familiar narrative of that memoir, as well as an exhaustive record of fact.

Many of these factual matters are in some ways trivial, and Marable, who died days before the book was published in the US, was lucky to avoid interviews about some of the more tedious ones. Malcolm's criminal record in Boston was not, it seems, as grand or ignominious as he claimed (he was a thief, pusher and pimp), and he had a brief career as a club act under the name "Jack Charlton". He was also, briefly, a waiter at the Parker House, where Ho Chi Minh had some years earlier been a pastry chef. (The hotel is now a property of the Omni luxury hotel group and has not produced any known revolutionaries since.) In prison before his conversion, he ate large amounts of nutmeg for its psychedelic effects; the paranoia, depression and hallucinations it caused might have been related to his first flirtations with the divine. He cursed God, and the other inmates nicknamed him "Satan".

Marable rightly attacks Malcolm's claims about having learnt wickedness from the "cesspool morals" of white women, pointing out that he seems to have downplayed his own innate talents for beating women and lying to them. Slightly more intriguingly, Malcolm himself - and not his supposed friend "Rudy" in The Autobiography - was embroiled in a long-term kinky affair with a prosperous white man who employed him as a butler. Malcolm later married and fathered six daughters, but he was at least uneasy with his sexuality even in married life and confessed frustration with marital life to his boss and spiritual mentor, Elijah Muhammad.

It is difficult to avoid concluding that Malcolm sublimated a great deal of energy into what seems to have been an insanely taxing schedule of travel and preaching on behalf of Elijah Muhammad's organisation, the Nation of Islam, which Muhammad ruled dictatorially, and whose funds provided him in turn with several houses and pieds-à-terre for his mistresses. Marable's narrative greatly surpasses Haley's in conveying just how strange and heretical that organisation was and in most ways continues to be, resembling Islam only in name and in its prohibition on pork and alcohol. Elijah Muhammad's trip to Chicago from Detroit is described as its "hijra", and its followers were at one point commanded to pray facing Chicago.

Founded by Wallace Fard, an itinerant salesman, in 1929, it grew not out of Islam per se but out of Marcus Garvey's Back to Africa movement and a series of indigenous black religions in the United States, including the Moorish Science Temple. The heresies against mainstream Islam multiplied through the years, until Fard's successor, Elijah Muhammad, declared that Fard claimed to be not only a prophet but God himself. Elijah Muhammad then wedded heresy to sleaze, bedding no fewer than six of his secretaries at a time while Malcolm worked the circuit as the Nation of Islam's most recognised spokesman. In The Autobiography, as in this biography, the most moving passages are Malcolm's break with the Nation of Islam during the last six years of his life. The story is, in Marable's telling, a ballad of cruelty and kindness: cruelty on the part of the Nation of Islam, which demoralised and sanctioned its most devoted and charismatic servant, and kindness on the part of the broader Muslim world, which welcomed Malcolm with what now seems like remarkable forbearance, given the blasphemy of the doctrine he represented. As Malcolm acquired his own voice, the charmless and wizened Elijah Muhammad made efforts to undermine him, notably, Marable says, by humiliating him with public references to his sexually unsatisfying marriage.

Compare this to abuse the warm reception Malcolm received in Cairo in 1958, when he arrived as a guest of Gamal Abdel Nasser. The sheikhs of Al Azhar accepted him warmly, overlooking his plain idolatry of Wallace Fard and Elijah Muhammad. Malcolm himself admitted he had "only a sketchy notion" (read: none at all) of Muslim prayer and zero Arabic. A visit to Saudi Arabia on the same trip, four years before the abolition of slavery there, left him perplexed, deeply unsettled by the realisation that the black-white divide he preached and lived in the US was not the only way by which Muslim populations were segmented.

In 1964, when Malcolm's split from the increasingly discredited Elijah Muhammad was becoming definitive, he performed Haj, which Haley and popular wisdom generally credits as the completion of Malcolm's redemption and the cause of his ultimate renunciation of race-based separation. "Islam brings together in unity all colours and classes," he wrote. "I began to perceive that 'white man', as commonly used, means complexion only secondarily," and that colour mapped imperfectly to goodness. On the same trip, he visited Muslim Brotherhood representatives in Beirut and enjoyed the adulation of crowds in Cairo and Alexandria (the result, Marable says, of the publication of a photo of him with the US boxer Cassius Clay, later to become Muhammad Ali, in Egyptian newspapers).

About Malcolm's assassination the next year, there has been much speculation, to which Marable adds the most damning evidence thus far. During a public address in Harlem, one man created a diversion while three others stormed the stage and shot him dead. Three men were convicted, but Marable claims two were probably innocent - and what's more, US law enforcement agents knew the hit was due, but failed to warn anyone because they didn't want to blow their cover, and because they might not have much wanted Malcolm to live anyway.

Assassination has its privileges: even Marable, a biographer who is relatively unflinching, is not above canonising Malcolm as a "secular saint", an American martyr for a particular form of freedom and liberation. But it's worth noting, too, what Malcolm did not achieve. The personal achievement is remarkable, and even the disenchanted version of Malcolm we get in this biography is a man who has completed a longer religious journey than most, graduating from low-grade villainy as a youth to something approaching humility and transcendence at the end. The political achievement is less impressive: Martin Luther King, Bayard Rustin and A Philip Randolph were on the streets during the same time but didn't pollute their work with violent rhetoric, or effusive praise of a womanising fraud. One wonders if the later, inclusivist Malcolm would have accomplished as much, if he had lived beyond 39.

Graeme Wood is a contributing editor to The Atlantic.