Arab motifs have decorated Venice for centuries, evidence of enduring ties between the city and civilisations to the East.

At the 2013 Venice Biennale, Arab artists and those from the broader Islamic world are back as never before. The work ranges from stained glass to video, from solemn to satirical.

Welcome to Iraq, the Iraqi pavilion that for the first time presents the country’s contemporary artists at the Biennale, was not in the clusters of national exhibitions at the public gardens (giardini) or at the vast Arsenal, a former naval fort. But the Iraqis were on the Grand Canal, in Ca’ Dandolo, a 16th-century palazzo.

Objects on view reflected a spectrum of styles, none of which would have cost much to create. Furniture was fabricated by Akeel Khreef from scrap metal and bicycle parts. A room by a duo calling themselves WAMI was decorated entirely in cardboard, including cardboard blankets and a cardboard water pitcher. The exhibition’s sturdy tote-bag, the most durable in the entire biennale, was emblazoned with a Welcome to Iraq logo, and a cartoon by Abdul Raheem Yassir depicting policemen with machine guns searching a man with his hands held high. Unbeknown to the officers, one of those hands holds a pistol.

The pavilion’s curator, Jonathan Watkins, the director of Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, England, acknowledged that security and economic reconstruction were Iraq’s priorities today. “Maybe art is further down the list,” he said.

Another display showed a 300- year old cracked ceramic vessel, with honey frames from a beehive suspended above it on a rope. Furat Al Jamil called it Honey Pot. She explained that her cat had knocked it over. “The honey,” she said, “is our hope that our heritage can heal.”

Showing Iraqi art in Venice, she said, “inspires others to be more productive and more inventive, and to actually believe that they can be in such a place”.

The pavilion is supported by the Ruya Foundation for Contemporary Culture in Iraq. One of Ruya’s founders is Tamar Chalabi, the daughter of the Iraqi politician Ahmed Chalabi.

Iraq’s presence in Venice, said another Ruya donor, Shwan Ibrahim Taha, “means that we are alive. We’re not dead. That we are culturally significant. Iraq is the cradle of civilisation and I beg everyone not to make it the grave of civilisation. This is the continuation of culture in Iraq.

“For us to put this together was a logistical nightmare,” said Taha, whose financial firm, Rabee Securities, helped sponsor the show. “I am always asked why you would have art at a time when people are dying. We could today just pay attention to feeding people and building buildings. If we ignore our culture and just concentrate on the infrastructure, we will wake up with a country that we don’t know, that’s soulless. As much as it’s important to bandage the wounds and build the body, it’s very important to have a continuation for the soul.

“The seeds are there now for it to grow,” he said, noting plans under way to tour the exhibition throughout Iraq.

At the Palestinian exhibition – not a pavilion, since the Biennale does not recognise Palestine as an independent state – the ordeal of the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza arises again, in the form of an “occupation” created by members of the public in the spacious leafy garden behind the ground floor of an art school in the Dorsoduro quarter.

Visitors tend to find the unpublicised show by accident. Each guest is asked to take a cardboard box and is given a knife to cut windows, decorations and anything else into the generic container. The visitor-architects can then place the box, with its ornamentations, in ensembles of containers that resemble settlements in the Occupied Territories.

As the number of boxes multiplied, so did the variety of designs on them – faces, Islamic motifs, slogans, even animal shapes.

The idea for Otherwise Occupied came from Bashir Makhoul, the Palestine-born artist who is also director of the Winchester School of Art at Southampton University in the UK. Makhoul will take the elements for the improvised settlements to the Tokyo Biennial later this year. A video by Aissa Deebi is also part of the exhibition.

Otherwise Occupied is the second time that Palestine has been represented at the Biennale. In the first, in 2009, the exhibition was organised officially. “This year we got a letter from the Biennale saying that we cannot use the name ‘pavilion’,” said Rawan Sharaf, the director of Palestinian Art Court (Al Hoash) in Jerusalem. “We are a ‘collateral event’.” The curators and artists of Otherwise Occupied stress that their exhibition is funded independently, not by the Palestinian Authority.

Despite minimal publicity, the flow of visitors from the streets has been constant, as cardboard structures crowd the garden with dense “settlements” stacked upon one another. Heavy rains in the early days of the Biennale forced Sharaf and her team to remove some boxes that began to decompose. Visitors were quick to fill the gaps.

Nearby, in galleries that faced a radiant southern sky, Saudi artists from the group Edge of Arabia were showing their work in a museum of archives. The Saudi exhibition, Rhizoma (Generation in Waiting), was also not an official site, said the show’s London-based Iranian curator, Sara Raza. Unofficial status helped account for its strong dose of satire.

It also made room for the graffiti-inspired cartoons of Omamah Ghassan Asem Alsadiq, 22, whose spray-painted camel was at the entrance. Camels decorate the business card which identifies the young artist as a “freelancer graphic, interior designer”. She admits that similar camels are drawn on the streets back home. “We spray and run, and we manage not to get caught. It’s illegal,” she said. “I’ve done 150. If you go to Instagram, you’ll find them.” Media exposure in Venice could take her art from the street into commercial galleries.

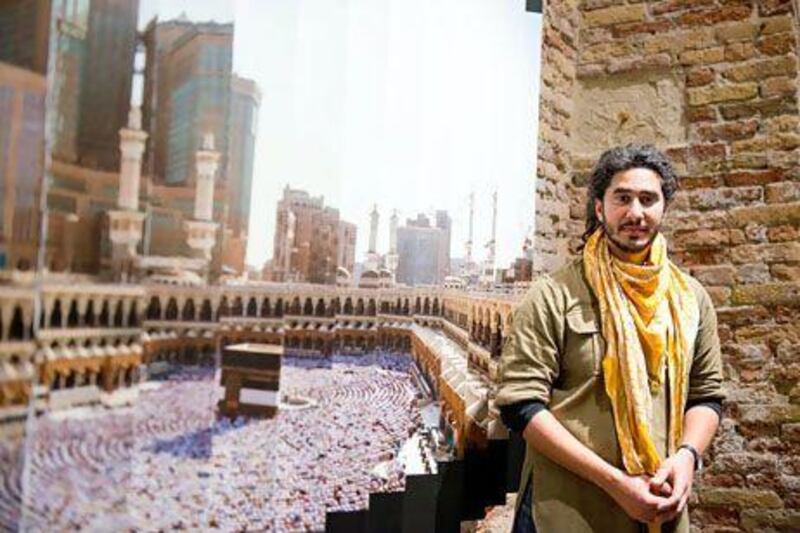

Saudi streets were also the subject of a lenticular photograph (pictures cut into strips and reconstituted into a single print) by Ahmad Angawi, which showed a traditional view of Mecca from one angle and a view of the city choked with new high-rise architecture from another.

Rows of low uniform wooden columns in an installation by Eiman Elgibreen revealed human female faces underneath when visitors lifted the columns.

“These artists are from the YouTube generation that’s concerned with new-media practices,” said Sara Raza. “But we are also seeing the revival of craft,” she noted, as the artist Nasser Al Salem created a work of calligraphy on the wall behind her.

Arab artists were not limited to Arab exhibitions. At the Maldives Pavilion, Khaled Ramadan of Lebanon showed a no-budget documentary tracking recent troubles in that Indian Ocean archipelago and the Egyptian Khaled Hafez’s video addressed a particularly Venetian subject: water.

On the edges of the Arab world, kinships among artists crossed borders. And artists from Arab lands with limited exposure to the world of contemporary art saw the unexpected. Bassim Al-Shaker’s paintings of rural life in Iraq’s southern marshlands may have evoked the landscape of the Venetian lagoon, but they couldn’t have been more traditional. As Al Jamil translated, he told of spending a day in the pavilions of the giardini: “I was very impressed with what I saw. I was inspired. For me, it was all new.”

The Venice Biennale continues until November 24. Visit www.labiennale.org/en/art for more information

Follow us

[ @LifeNationalUAE ]

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.