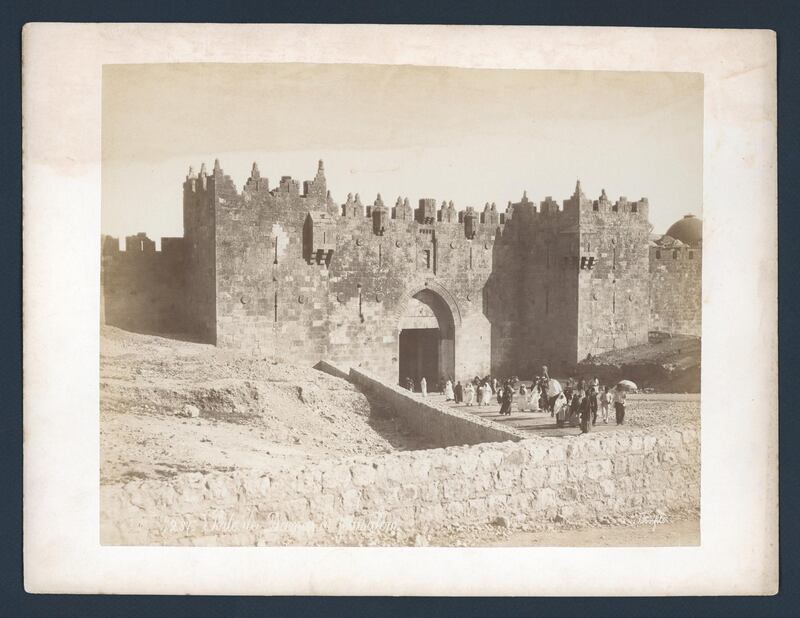

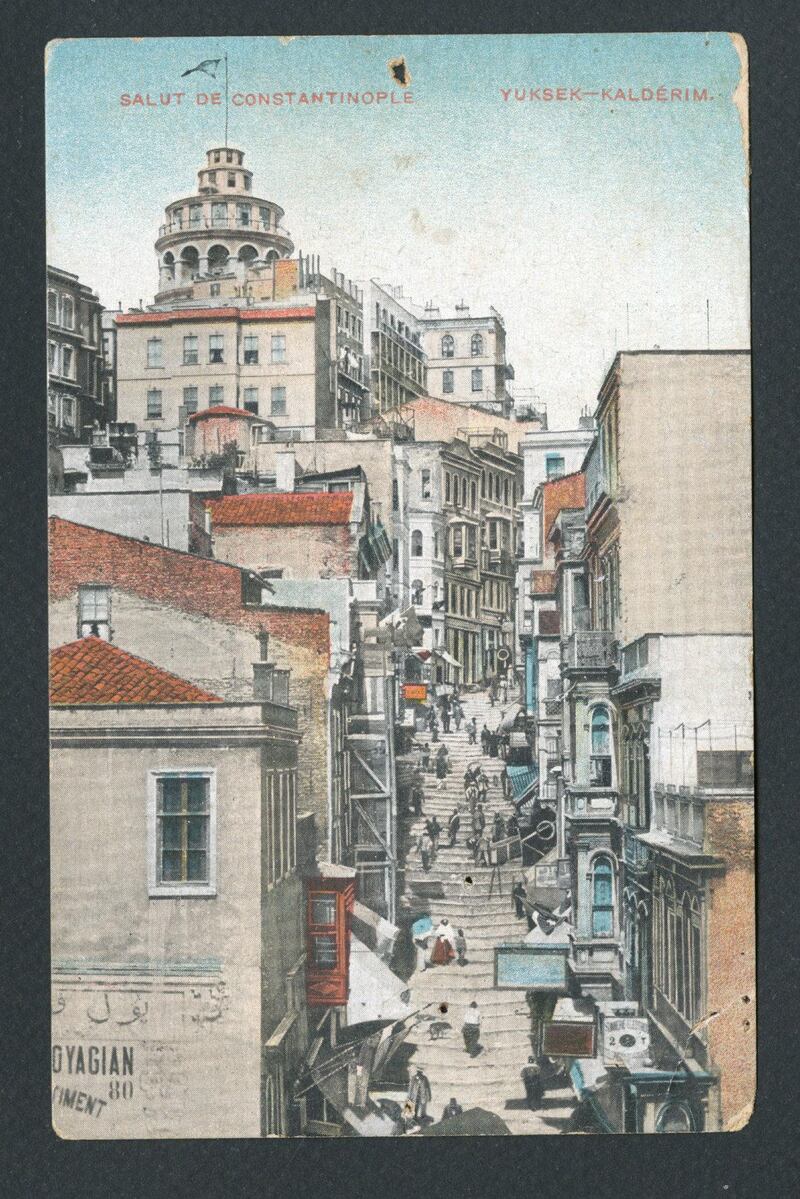

Carrying an empty suitcase and petty cash, Ozge Calafato flew to Turkey with one goal: gather as many photographs as possible. Visiting markets and antique shops in Istanbul and Izmir, the archivist found images from periods such as the late Ottoman era and the Turkish republic, eventually bringing 16,000 photographs back to the UAE.

Her collection, part of which has been digitised, is now part of the archive at Akkasah, the Centre for Photography at NYU Abu Dhabi.

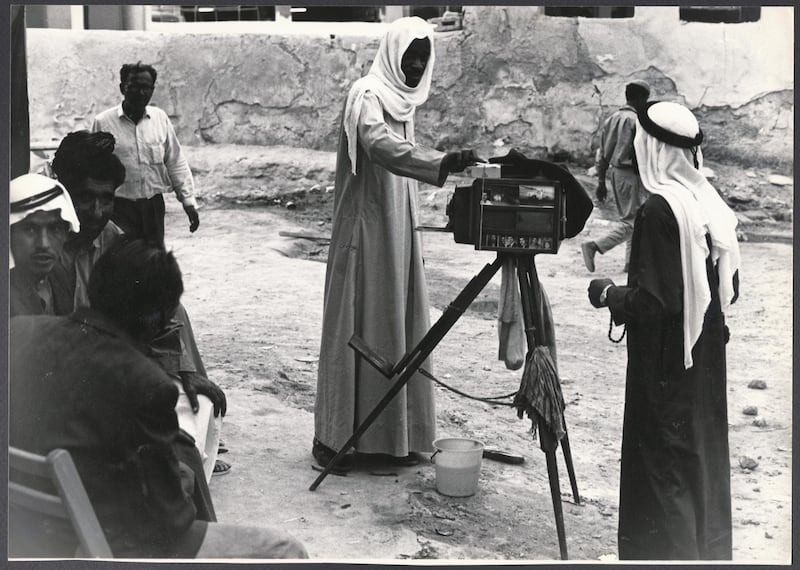

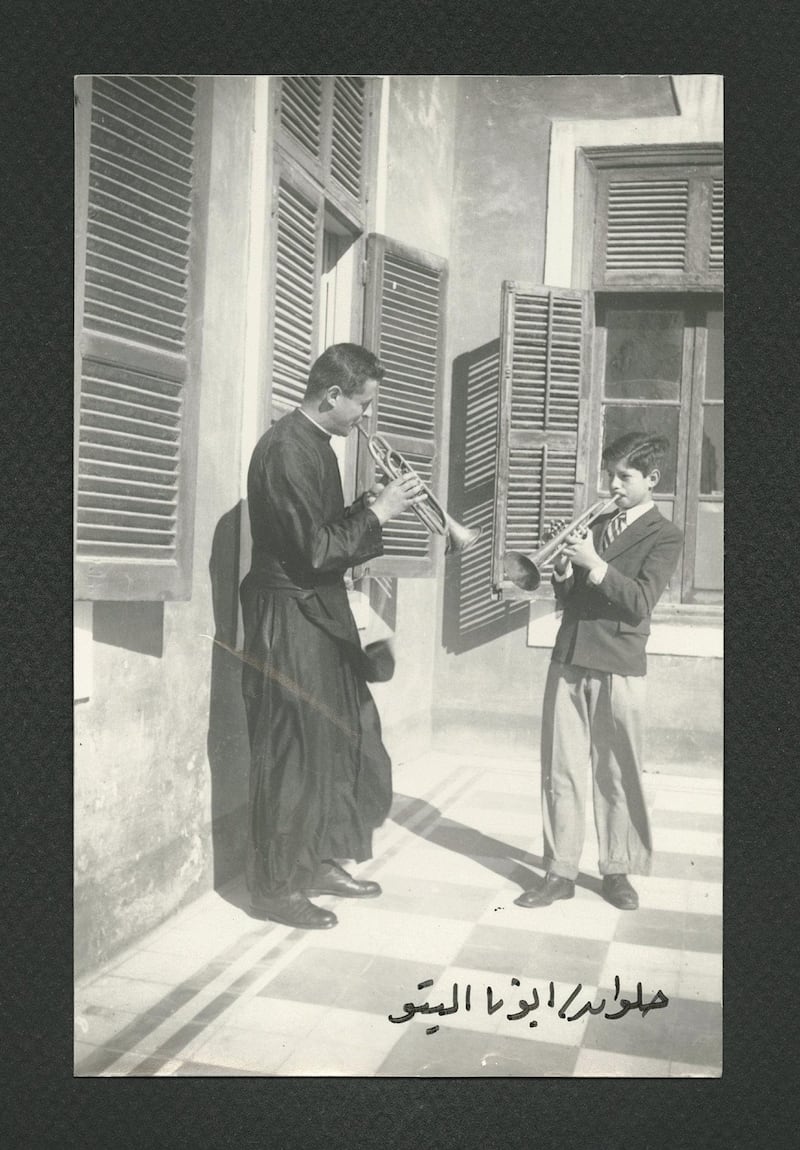

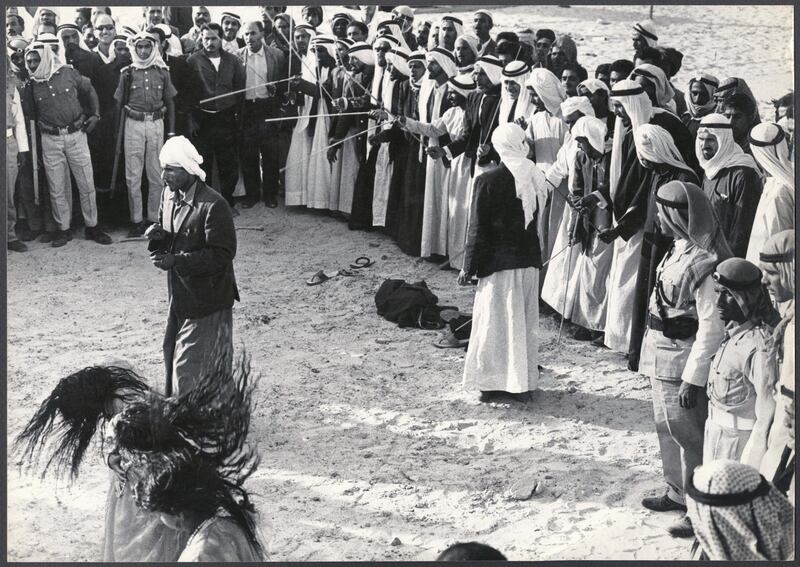

Named after the Khaleeji term for “camera”, the team at Akkasah collects vernacular photographs – everyday images often captured by amateurs and non-artists – from the Arab world. They then store these visuals in analogue and digital formats, where they are available to the scholarly and the curious, for research, documentation and general interest.

Calafato's collection was assembled specifically for the centre, where she worked as project manager from 2014 until this year. Shamoon Zamir, a professor of literature and visual studies at the university, started the endeavour, which now has about 33,000 analogue photographs in its records, and it has published more than 10,000 of those on its website.

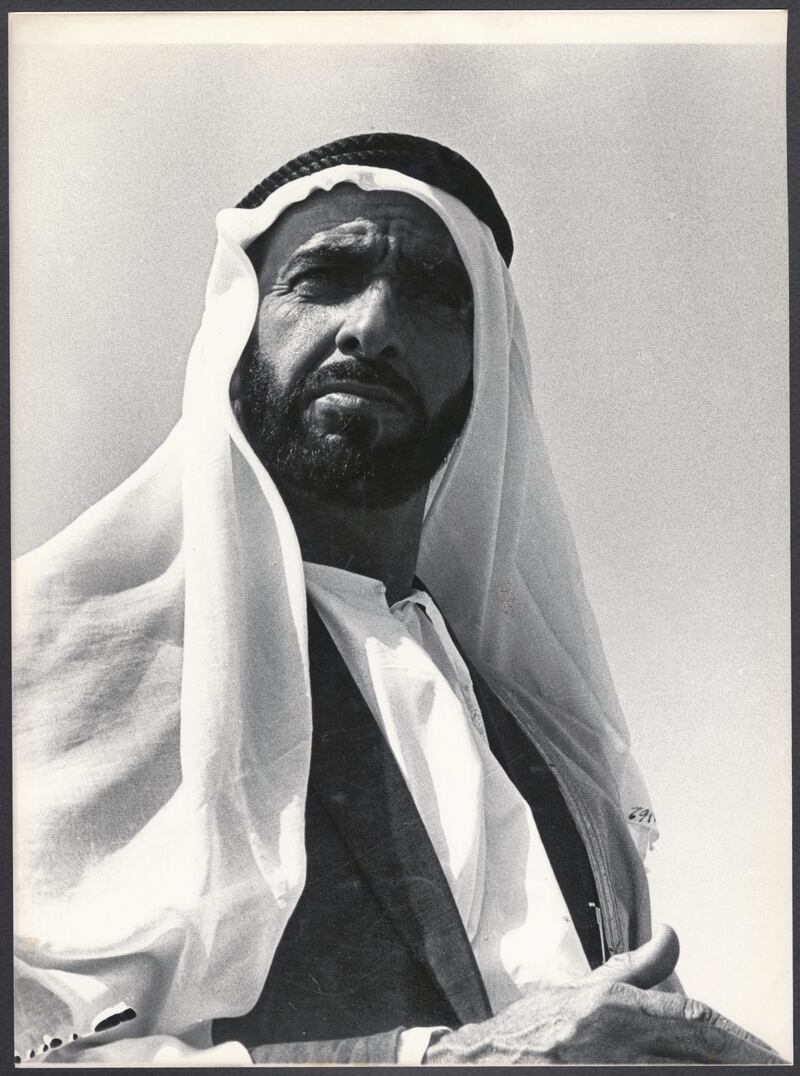

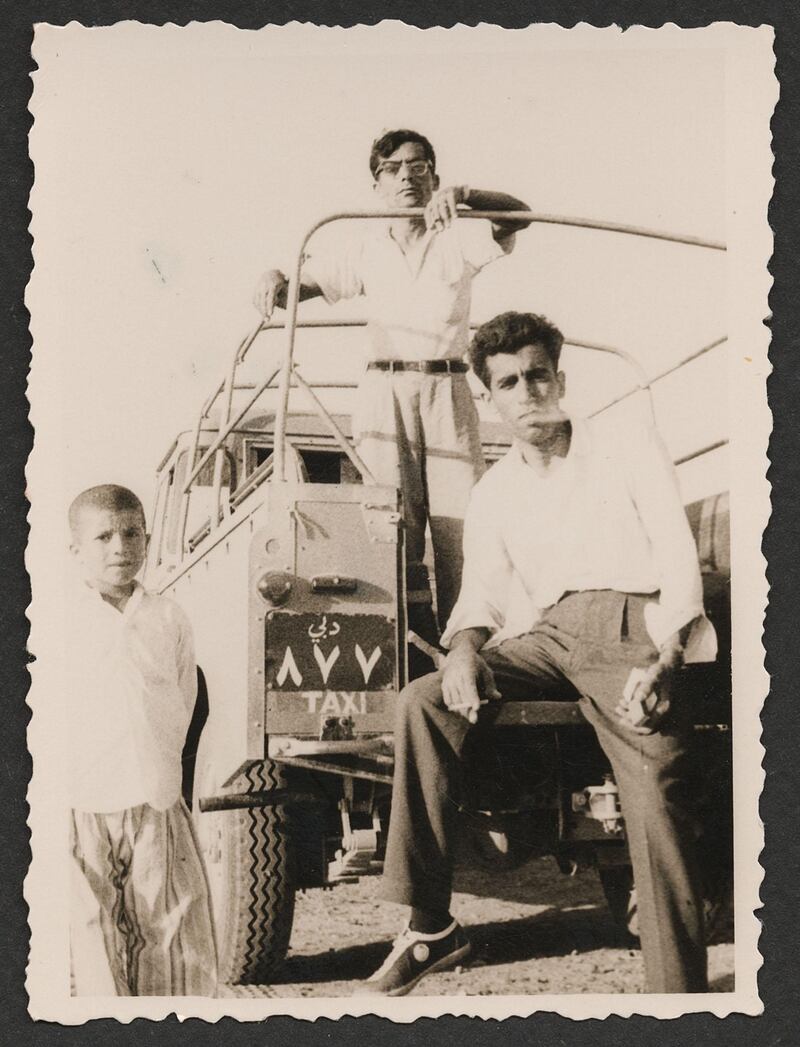

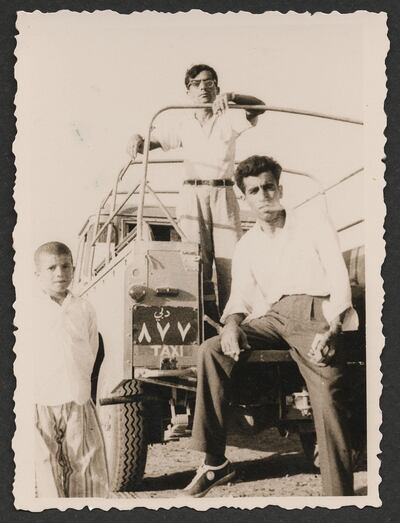

Within Akkasah's archives are a multitude of collections from across the Mena region, including Egypt, Sudan, Syria, Jordan and Palestine. One of its rarer collections comprises personal images from Abdulghafoor Al Qassim, a retired engineer from the Emirates. The 160 photos in his collection date back to the 1960s, when Al Qassim was a student in Dubai. "Getting an Emirati family to share family photographs was a breakthrough," Zamir says.

Akkasah was given the images through one of Zamir's former students. "I made sure the family understood they would have the right to refuse [permission] at every stage," he adds.

Akkasah ensures intellectual property rights remain with the collectors or donors, he explains. "I'm hoping that other students and then other families will see the collection and realise that we do it with a degree of respect."

For Zamir, the photographs offer invaluable insight into Emirati family life and culture, the rarity of which, he says, has affected the way younger generations perceive their history. "It is always surprising to me when I talk to some Emirati students who don't really know how people dressed in the 1950s or 1960s in the UAE," he says. "They didn't always have a very clear sense of their own past because they did not have the resources to easily go outside of family albums."

With the growing archive, he says he hopes this will start to address the issue.

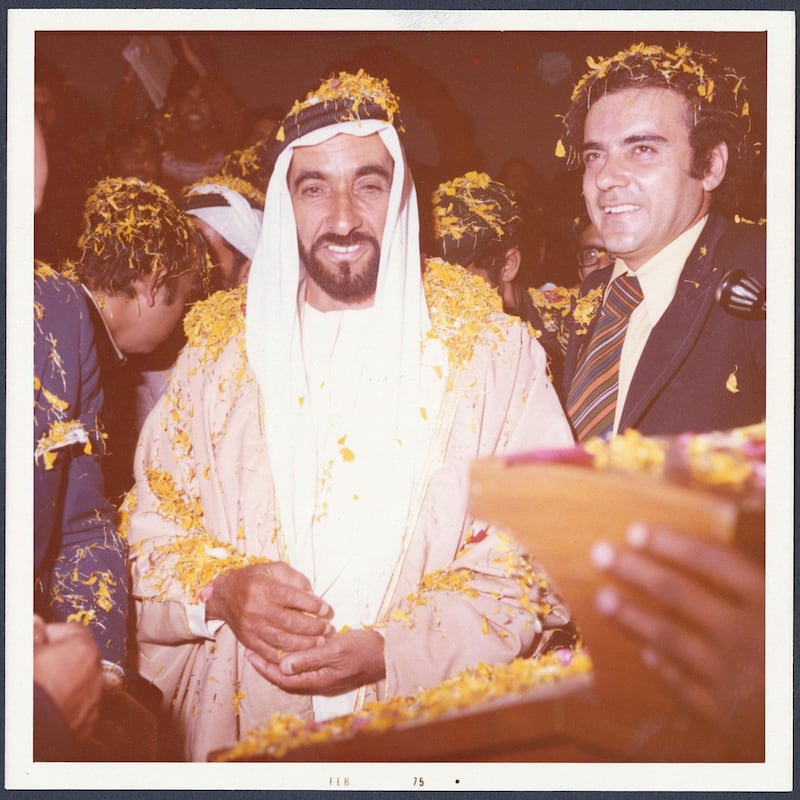

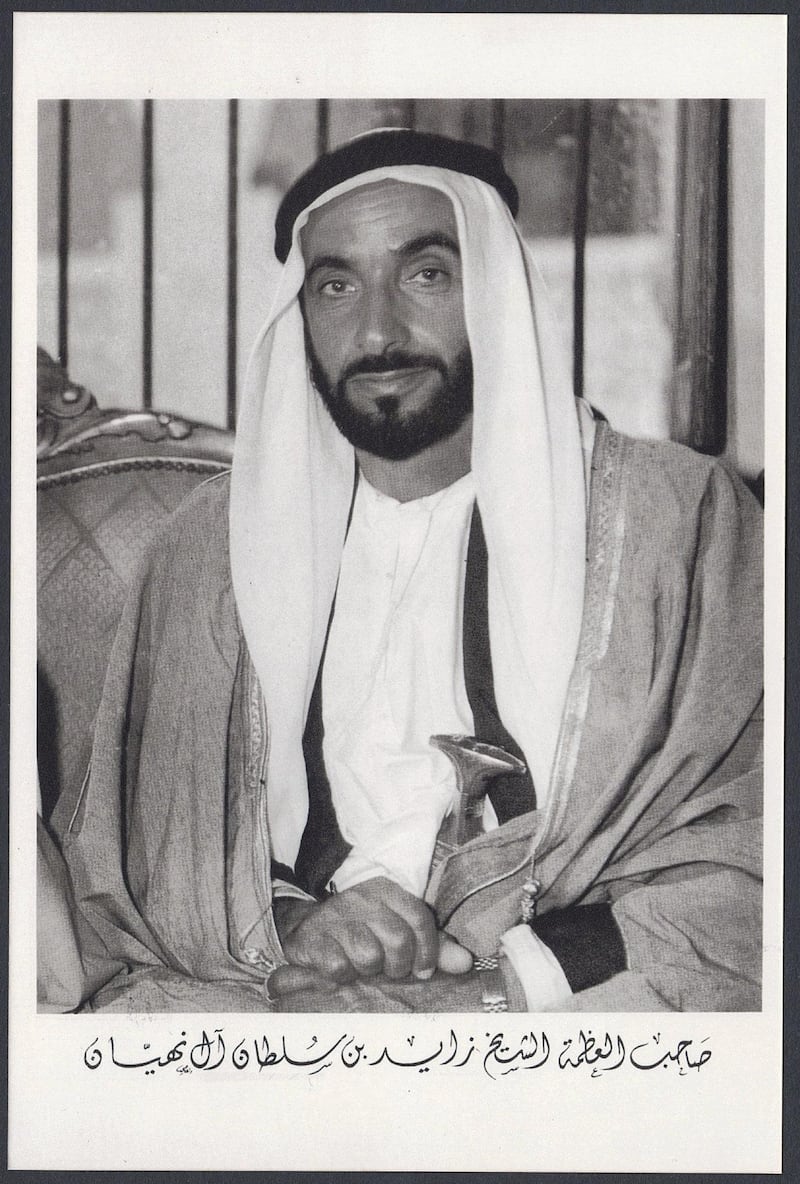

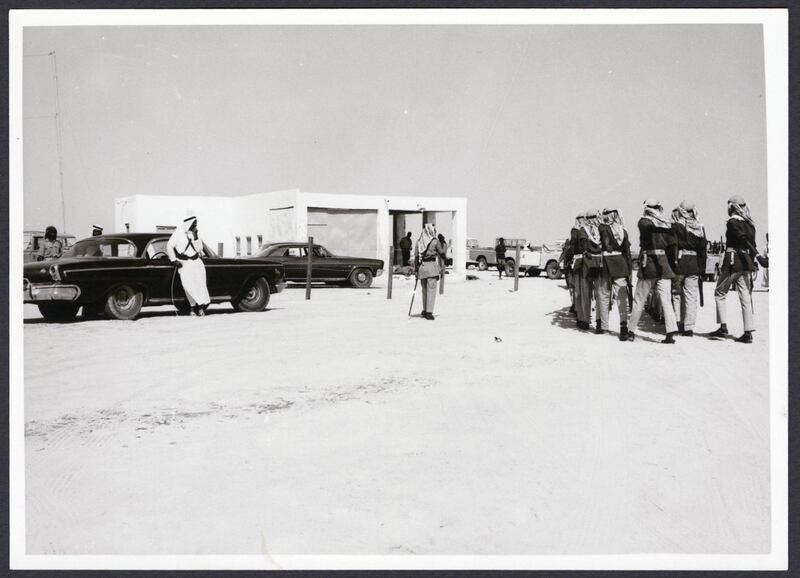

Another set of visual records about the country comes from Zaki Nusseibeh, Minister of State, who served as an aide and adviser to Sheikh Zayed, the Founding Father. Nusseibeh's collection shows UAE leaders meeting dignitaries across the world, as well as street scenes from Abu Dhabi in the 1970s.

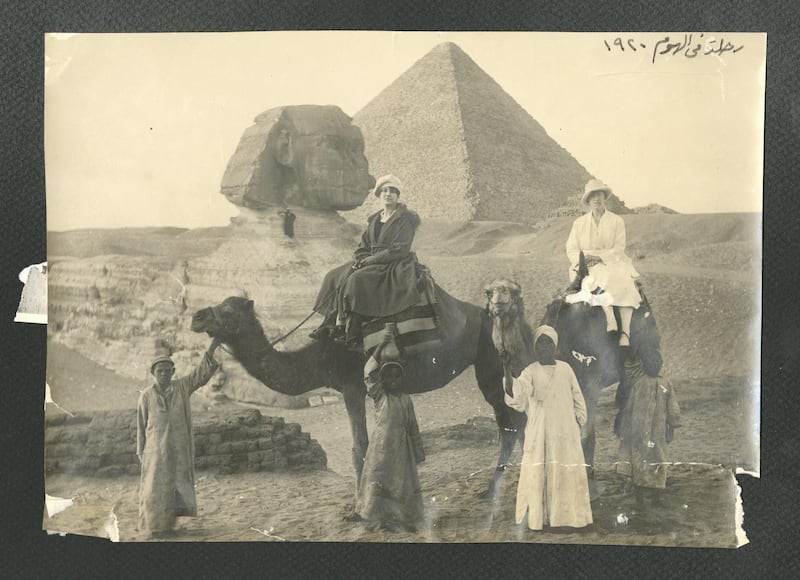

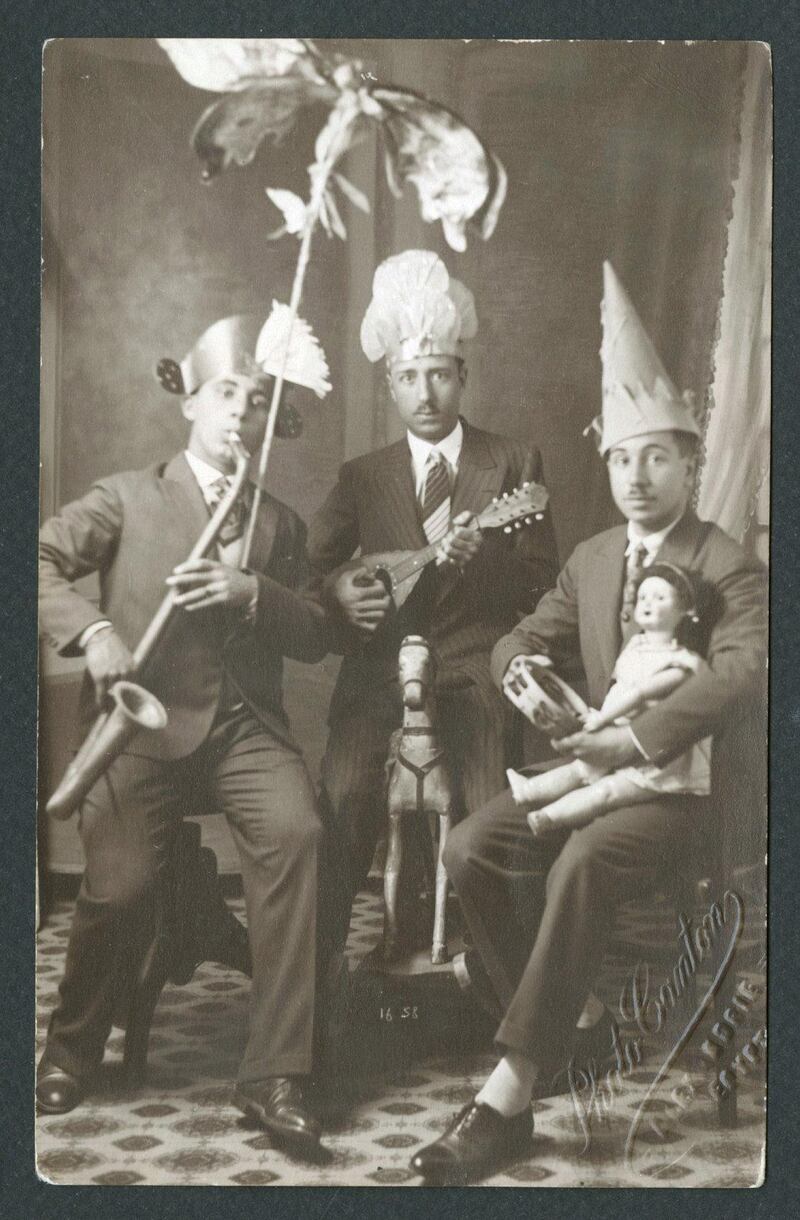

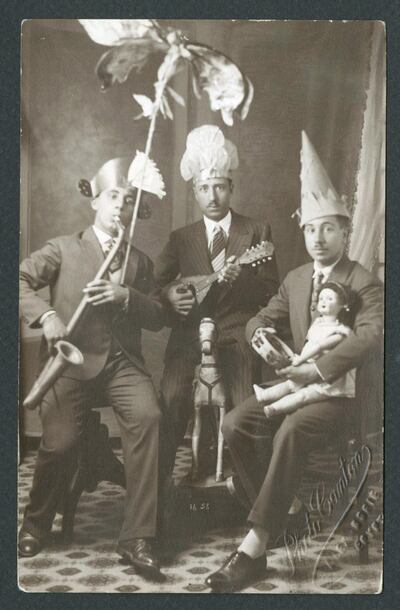

Akkasah's first acquisition comes from photographer Yasser Alwan, who built his own collection of about 3,000 images featuring formal studio portraits, family pictures and everyday snapshots of Egypt and Sudan, from the 1920s to the 1950s.

Despite the sheer volume of photographs in Akkasah's trove, their origins and the stories behind them largely remain a mystery. The role of the centre's team is not necessarily to dig up all the narratives in these pictures, but to provide the correct metadata to classify and categorise them in a clear manner for researchers and the public to sift through.

Because the sources of many of the photographs are unknown, the team avoids drawing conclusions that cannot be fact-checked. "We generally only put in information … that can be gleaned from the object itself," Jonathan Burr, an assistant archivist, says.

He offers the example of a picture of a man holding a child. "You would assume that's a father and son, but we would never put that because it might be an uncle. We don't know." Instead, he says, "we will describe the points of potential interest for researchers".

Even the process of scanning images raises specific issues. When dealing with damaged materials, for instance, should archivists restore them or present them as they were found? When scanning negatives, how do they decide on elements such as contrast and brightness? When presenting albums, should they retain the order of the images as the owner arranged them? According to Calafato and Burr, these are all "ongoing negotiations".

"When digitising negatives, there is the question of trying to present the image in a way one would imagine the creator of the image would have intended it," Burr says, citing the example of the Samir Farid Collection, named after the Egyptian writer and film critic. The collection contains images shot on the sets of Egyptian films, some meant for publicity or movie posters.

The archivists could then assume these were meant to be shown in pristine condition, so would do their best to remove minor damage.

But the team would not try to restore the pattern of a dress in a damaged photo, as that would require a certain level of artistic interpretation on the part of the archivist. "It is about acknowledging the limits of our own scholarship" Burr says. "Part of it is simply that we do not want to overextend into a realm that belongs to different scholars and researchers."

Most recently, Akkasah commissioned projects from artists whose works investigate the UAE and the Gulf. These include Philip Cheung and Xyza Bacani. Cheung's series, The Edge, captures the ever-changing coastal landscape of the Emirates, which has been affected by fishing, pearling and the shipping trade. Bacani, known for her street photography, presents a documentary project titled Komunidad: Filipinos in the UAE, which shows the daily lives of workers who hail from the Philippines.

Zamir says he recognises the projects’ value in terms of “documenting the current realities of the UAE because they, too, would become historical materials very quickly, given how this country is changing”.

As the centre reaches its sixth year, the archivists are still busy collecting, digitising and labelling images. Zamir hopes Akkasah will continue to add to NYUAD's legacy in the region, creating a valuable resource tool for researchers today and in the future.

"One of the truly important contributions that NYU Abu Dhabi can make to the region … is to help preserve the collective memory of the culture, the society and the history," he says. "Much of this relies not just on written records, but visual materials."